Unserdeutsch corpus available in the DGD

By Siegwalt Lindenfelser.

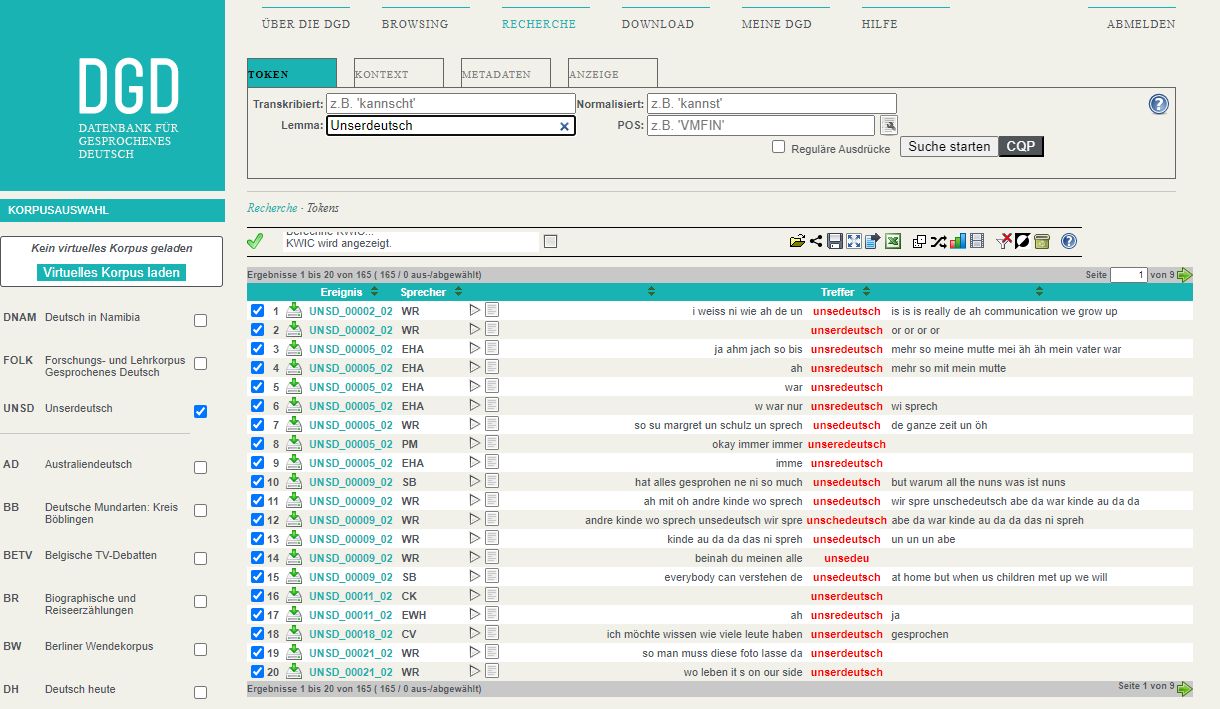

Version 2.21 of the Database for Spoken German (DGD) from January 2024 includes the first release of the corpus “Unserdeutsch” (UNSD). In addition, the corpus is now also available via the ZuMult tools at the Institute for the German Language (IDS)

Building up the corpus with EXMARaLDA tools

The corpus was created entirely with EXMARaLDA tools, from the transcription of the speech recordings to the normalisation and lemmatisation of the transcripts and the part-of-speech tagging. The corpus compilation and processing in the DFG project “Unserdeutsch (Rabaul Creole German): Documentation of a highly endangered creole language in Papua New Guinea” (Prof. Péter Maitz, Prof. Werner König) at the University of Augsburg and later at the University of Bern was carried out in close cooperation with the Archive for Spoken German (AGD) and the developer of the EXMARaLDA tools, who at that time also held the position of head of AGD and the superordinate programme area Oral Corpora at IDS. In turn, suggestions for further development of individual EXMARaLDA tools flowed back from project-specific requirements.

The first and probably last larger corpus of Unserdeutsch

The Unserdeutsch corpus as now published provides audio recordings, cGAT transcripts and metadata on more than 50 events totalling over 50 hours in the only German-based creole language. Unserdeutsch is critically endangered and is only spoken by under 100 older people on the east coast of Australia and in Papua New Guinea. The biographical interviews collected between 2014 and 2018, which mainly make up the corpus, document a structurally unique variety shaped by intensive language contact and, in terms of content, a piece of German colonial history.

The place of origin of Unserdeutsch: Vunapope mission station, Papua New Guinea

(Photo: Siegwalt Lindenfelser 2017)

Unserdeutsch originated at the beginning of the 20th century among ethnically mixed children and young people in boarding schools run by the Catholic Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC) in Vunapope on the island of New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago. This was part of the colony of German New Guinea from 1884 to 1914. The children and young people, mostly half-orphans, were brought to the mission station and educated in German as part of the MSC’s Christianisation policy – not always voluntarily or with the consent of their indigenous mothers. Most of them brought with them an early form of Tok Pisin as their first language, the current lingua franca and national language of Papua New Guinea, which is itself an English-based Pidginkreol. Ethnically uprooted and under the pressure of having to speak German despite not yet having sufficient competence, Unserdeutsch emerged through the interplay of language contact and L2 effects – and stabilised, although competence in spoken and written Standard German was also acquired later. Through intermarriage, Unserdeutsch was passed on to the second generation as a first language, survived the turmoil of two world wars and was later further shaped by increased language contact with English (for more information on the genesis of Unserdeutsch, see Lindenfelser 2021). The last remaining speakers of Unserdeutsch don’t have any more parallel competence in the standard an show more or less pronounced indicators of language attrition, since they are rarely using the language in an English-dominant environment.

Challenges in transcription and annotation

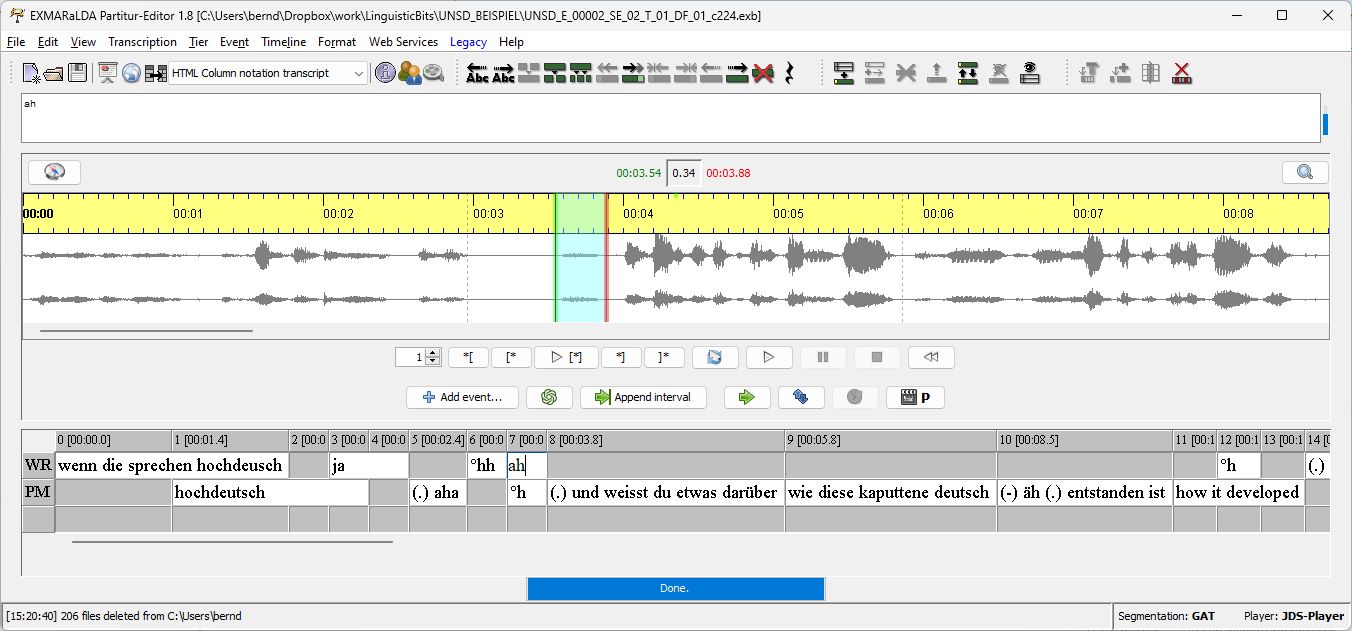

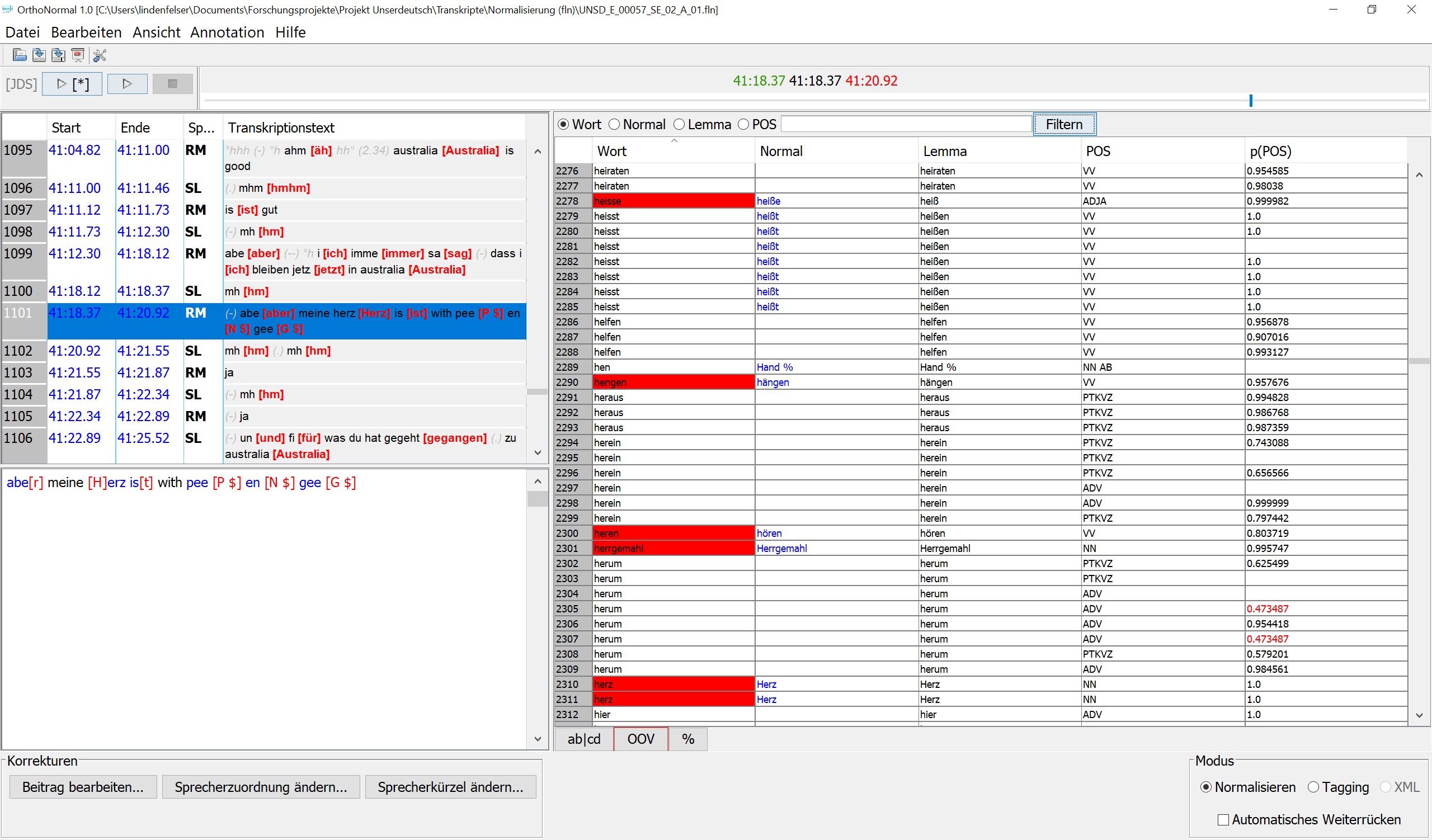

Due to the intensive language contact between three languages in the data – Unserdeutsch, English, Tok Pisin – the construction of the Unserdeutsch corpus required a series of upstream decisions during transcription and annotation (for more details on the corpus construction, see Götze et al. 2017). The transcription was carried according to cGAT using the EXMARaLDA Partitur-Editor, whereby the principle of using only lower case in the minimal transcript was broken at one point in order to be able to represent the difference between Unserdeutsch i ‘ich‘ and English I ‘ich‘. The tokenisation of the transcripts for import into OrthoNormal was carried out using the FOLKER editor. Finally, normalisation, lemmatisation and part-of-speech tagging were carried out in the EXMARaLDA tool OrthoNormal. A critical number of transcripts were first semi-automatically pre-tagged on the basis of a parameter file for spoken German and then corrected manually in a more time-consuming process. The developer then trained a specially customised parameter file for Unserdeutsch on this basis and implemented post-processing rules that significantly reduced the manual correction effort from this point onwards. POS tagging in Unserdeutsch was carried out on the basis of the STTS 2.0 tagset, with a set of additional project-specific rules. These included, on the one hand, the introduction of new tags (PTKAM for the aspect particle of the am-progressive, which is strongly grammaticalized in Unserdeutsch, as well as PL for the analytical plural marker alle in Unserdeutsch: alle Haus ‘Häuser‘). On the other hand, existing tags were extended (e.g., a specification of the tag FM ‘Material from other languages’ according to language such as FM-TP for Tok Pisin) or reduced (e.g., an underspecification of verbal tags which omits the information on finiteness which is problematic for Unserdeutsch – VVFIN and VVINF were thus merged into one tag VV). This also played a role when adapting the parameter file and the post-processing rules to project-specific requirements. Last but not least, to facilitate the manual correction during corpus compilation, the developper introduced some smaller convenience features to OrthoNormal, such as a running number for tokens.

Annotation of a tokenised Unserdeutsch transcript in OrthoNormal

Before the corpus data was transferred to the IDS Mannheim, the EXMARaLDA tools COMA for creating a locally searchable corpus and EXAKT for searching within the locally created corpus were also used for internal project searches. Unserdeutsch is thus a use case that utilises the functionalities of the EXMARaLDA system in their broad diversity and at the same time has contributed to their further development, particularly with regard to the multilingualism of the data and the typologically divergent profile of the Creole language. The further processing of this data at the AGD and its publication via the DGD now enables in-depth, and in particular quantitatively sound, research into Unserdeutsch. The data still holds a great deal of untapped potential for further linguistic insights into language contact, language variation and language change, but also beyond this, for example for research into language acquisition or missionary, colonial and post-colonial history.

References

Götze, Angelika / Lindenfelser, Siegwalt / Lipfert, Salome / Neumeier, Katharina / König, Werner / Maitz, Péter (2017): Documenting Unserdeutsch (Rabaul Creole German): A workshop report. In: Maitz, Péter / Volker, Craig A. (eds.): Language Contact in the German Colonies: Papua New Guinea and beyond [= Special issue of Language and Linguistics in Melanesia], 91–142. [https://boris.unibe.ch/121389/]

Lindenfelser, Siegwalt (2021): Kreolsprache Unserdeutsch. Genese und Geschichte einer kolonialen Kontaktvarietät. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter. [https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110714067]